On 12 June, Kerrewin van Blanken will defend his dissertation Diplomatic Propaganda in the Dutch Republic and France, 1609-1674 at the University of Amsterdam. On the occasion of this event, the Huizinga Institute will host a masterclass by prof. Jason Peacey (UCL) on 13 June on the main theme of Van Blanken’s dissertation, the interrelationship between propaganda and international relations. Peacey is internationally acclaimed expert on this subject, and the author of books such as Print and Public Politics in the English Revolution (Cambridge, 2013).

The aim of the seminar is twofold. First, it seeks to acquaint participants with the scholarly debates and latest research on early modern public diplomacy and propaganda; second it seeks to challenge them to debate how such approaches to early modern political culture might be applied to their own research and/or other periods. Over the past years, scholars have studied the practice of ‘public diplomacy’, examining how (social) media were and are used by elite political actors to engage with audiences beyond, and affect international relations. This masterclass takes stock of some of the results of this research program, focussing on two questions for discussion.

- The effects of political print in Early Modern Europe

In the past decades, historians have stressed the emancipating potential of the printed new media in the early modern period. The rise of the new medium and new infrastructures of information was thought to have encouraged public debate and to have paved the way for liberal-democratic values. In recent years, this paradigm has been thoroughly revised. The print economy and new political media such as the newspaper increasingly studied in tandem with state building practices, and the technology of print as a tool for governance and control. How does research into public diplomacy contribute to this historiographical trend, and what new questions does it raise? And, given its strong reliance on state archives and a relatively top-down view of the media, what room is left for narratives of resistance and agency of individual readers and writers?

- Propaganda as knowledge

The history of knowledge is a relatively new research field that seeks to explain how historical groups and institutions create, codify, shared and evaluate knowledge. While initially coming out of the history of science, the history of knowledge has expanded into social and political terrain, with for instance histories of bureaucratic knowledge. Propaganda can be understood as attempts to utilize various psychological, sociological, rhetorical and technical knowledges for political ends. Central to the study of public diplomacy and propaganda in early modern Europe is the idea that, even though they were rarely codified into diplomatic handbooks of the time, these practices formed a kind of knowledge that could be shared, adopted and improved on by other diplomats. Are there indeed indications that specific forms of political knowledge of propaganda formed among early modern diplomats? What other types of knowledge did diplomats draw on in their evaluation of print propaganda? And did this knowledge spread beyond diplomatic actors as well?

Indicative programme

Doors will open at 12:30, with a sandwich lunch served. The masterclass concludes at 15:30.

Assessment and assignments

In order to obtain 1 ECTS, students prepare at least four discussion questions based on the readings.

Literature:

- Jason Peacey, ‘My Friend the Gazetier: Diplomacy and News in Seventeenth-Century Europe’, in: J. Raymond, & N. Moxham (Eds.), News Networks in Early Modern Europe (Brill, 2016) 420-442.

- Helmer Helmers, ‘Public Diplomacy in Early Modern Europe: Towards a New History of News’, in: Media History 22:3-4 (2016), 401-420.

- Nina Lamal, The Politics of Persuasion: Foreign Powers and the First Italian Newspapers’, Cuadernos de Historia Moderna 49:2 (2024) 261-277.

- Kerrewin van Blanken, ‘Introduction’. In: idem, Diplomatic Propaganda in the Dutch Republic and France, 1609-1674 (2025).

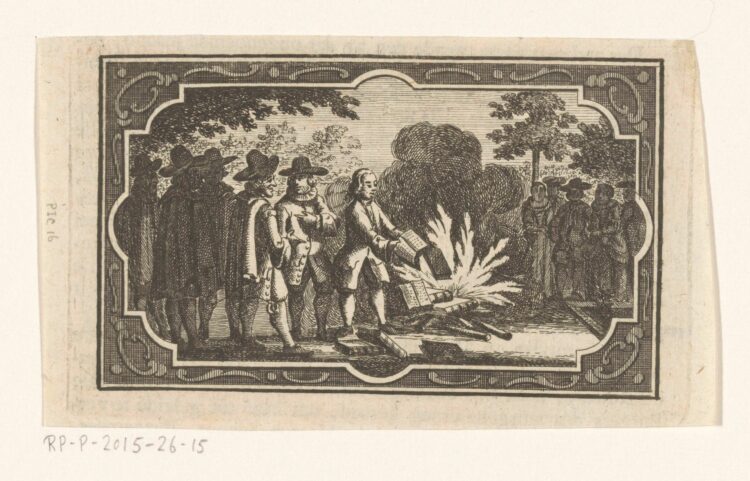

Book burning of De vera Religione, written by Socinian Johannes Volkelius, in the Amsterdam City Timber Yard in 1642. Anonymous print from 1780. Rijksmuseum

Register (0/20 spaces left)

This course is fully booked. For a spot on the waiting list, contact [email protected]